April 10, 2018; Washington Post (Associated Press)

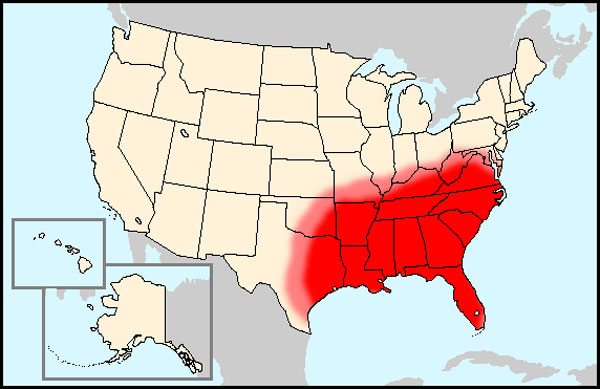

“The vision of an inclusive and thriving South is still elusive,” laments MDC in its newest State of the South report, “[as] we have substituted a culture of withdrawal for a culture of investment.” This 2018 report, “Recovering our Courage,” looks back over fifty years of progress and change in this swath of 13 states from Virginia to Texas while noting with dismay the region’s growing inequities and increasing disinvestment in the education and training essential to grow homegrown talent.

MDC was founded in 1968, the same year that Martin Luther King Jr was assassinated, to help North Carolina move from an agricultural to an industrial economy and from a segregated to an integrated workforce. Today, this nonprofit think tank gives us three lenses through which to assess the South’s progress and chart its future directions: belonging, thriving, and contributing:

Sign up for our free newsletters

Subscribe to NPQ's newsletters to have our top stories delivered directly to your inbox.

By signing up, you agree to our privacy policy and terms of use, and to receive messages from NPQ and our partners.

- Belonging: The black/white narrative is no longer sufficient to describe the South with its “growing racial diversity, immigration-driven population growth, increasing metropolitanization, and a stark political divide.” What’s needed is a new narrative about racial, economic, and geographic inclusion.

- Thriving: Across the South, black and Latinx populations have poverty rates as much as 20 percentage points higher than that of whites in the region. Higher-paying jobs are most often filled by newcomers with college degrees rather than by long-term residents. Deliberate institutional and community policies and practices could erase the region’s structural barriers to equity.

- Contributing: A decade of budgetary austerity means that almost all states in the South are investing relatively less in public schools and higher education than they were before the Recession. Substantial investments in education, employment, infrastructure and health—from both the public and philanthropic sides—are required.

The report ends with this plea: “We call on Southerners to reaffirm the values that have supported our progress, to weave again what has unraveled, and commit to realizing—together—a South where we all belong, where we all thrive, and where we all contribute to the place we call home.”

So where does philanthropy stand in helping to build a belonging, thriving, and contributing South? As NPQ has reported, big philanthropy is not investing in the deep South, particularly in on-the-ground work to promote systemic change. But there are an increasing number of bright spots where smaller Southern place-based funders are investing in strategic and collaborative systems change to promote more inclusive and equitable communities. Here are some examples:

- The Woodward Hines Education Foundation (WHEF) envisions “a Mississippi where all people can secure the training and education beyond high school that will allow them to enhance their quality of life, strengthen their communities and contribute to a vibrant and prosperous future for our state.” This grantmaker recently made a $900,000 grant to two of Mississippi’s 15 community colleges to build their capacity to respond to a systemwide problem with student retention and completion, particularly for first-generation and minority students. (Less than one-third of residents have attained an associate degree or higher, and less than a quarter have attained a bachelor’s degree or more.) Like other states in the region, Mississippi’s budget for higher education continues to be hacked—the community colleges got $28 million less this year than the last, and more cuts are anticipated next year when the state’s corporate and inventory tax cuts kick in.

- Greenville, South Carolina has been described as “one of the most difficult places in the country to climb out of poverty” despite being the fourth-fastest growing city in the US. The Hollingsworth Funds, a local foundation with assets of $356 million, is now a key supporter of the city’s Network for Southern Economic Mobility (NSEM), a long-term effort to change “the leadership, systems, and culture of the Greenville community as it relates to helping all members of our community climb the economic ladder and achieve their fullest potential.”

- The Benwood Foundation in Chattanooga ($102 million in assets) also focuses on eliminating barriers to opportunity and is investing in Chattanooga 2.0, “a cross-generational reimagination of public education” with the goal of ensuring that 75 percent of all Hamilton County high school graduates successfully obtain a college degree or technical certification by 2025.

- Last example: The Danville Regional Foundation ($218 million in assets) has taken the unusual step of regularly producing a “regional report card” that tracks key root cause indicators for education, health, socioeconomic status, and demographics, and compares the region to a comparable region (Wilson, N.C.), a model region (Owensboro, Kentucky), and to the State of Virginia as a whole. Upward and downward trends are visually displayed. As Karl Stauber, the Foundation’s president, explains, “We want to help spark a different and more significant conversation within our community—a conversation that is honest about our successes and our challenges across the region that leads to cooperation and collaboration building a healthier and prosperous Dan River Region.” This is clearly a powerful tool for conversation and accountability, particularly around opportunity. One can only wonder why the report card does not disaggregate the data by race. (The city of Danville is 56 percent people of color.)

MDC’s new State of the South report is sobering but crystal clear in its call to action, if the region is truly to be a place of opportunity for all. We can only hope that the points of light represented by the courageous and thoughtful investments by some Southern foundations are noted and emulated by other, bigger public and private players. Fifty years should be a time to celebrate, not lament.—Deborah Warren